Gilbert Reid Neilson

I am indebted to the dolvolturnocassino.it website as a source of information

Commando units recruited from among men already in the army but who showed the physical ability and the initiative to undertake 'special forces' work raiding behind enemy lines. Number 9 Commando recruited mainly from Scottish regiments, including Gilbert Reid Neilson, who was in the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders.

In the autumn of 1943 the battalion sailed from Liverpool to North Africa, then Italy where Allied forces were slogging their way up the Italian mainland having landed in the south. Tough German defence (Italy itself had capitulated) and terrain that lent itself to defence made progress very slow. Initially on the east coast, the only active mission was to land on two small islands in the Adriatic but they turned out to be unoccupied; this was undertaken by Number 2 Troop.

They were then transferred to the west coast of Italy to Bacoli where some were based in the castle:

British and American forces had reached the Garigliano River and while there were initial hopes to cross it quickly but the strength of the German positions and the awful weather caused second thoughts.

Only the 3D feature of Google Earth really shows what the Allies were up against as they fought their way up the country - from the mountains the Germanscould see any daytime movement. This view is looking north from above the front line of the Allies, the waves of the Mediterranean breaking on the beach on the left. The Garigliano is the muddy river running from the centre-right of the photo to the bottom left. The commando raid was to be on the flat land on the north bank.

A crossing on a wider front was planned and, somehow, a commando raid on the coastal area by the mouth of the river became an element of it - this was given the codename Operation Partridge. I have seen it said that the motive was to distract German attention and also to convince them this section should be reinforced - but as the British crossed the river here about two weeks later, neither of these really makes sense. I have the impression that the commandos were chomping at the bit and this was as good a mission as any.

The raid had three targets:

1. some higher ground on the seafront 2000 yards north-west of the river mouth (Monte d'Argento) - it's just visible in the photo above, right on the coast, a small dark green 'pimple' just where the 'white horses' of the waves end

2. a destroyed bridge carrying Route 7 (the Appian Way) over the river

3. a spit of land NW of the river mouth which separated it from the coast - visible in the photo as the area just where the river meets the coast

The three red stars show the targets. The Allies are advancing from bottom-right to top-left (Italy is not orientated north-south, as you might think!) and had reached the right-hand blue line, representing the Grigliano River

The plan was to travel by sea, land on the beach halfway between the objectives (so where the waves are breaking on the beach in the photo), then split into three parties. Allied forces south of the river would provide an artillery barrage on the targets, then the commandos would attack and occupy. They would then evacuate back across the river before daylight, in DUKWs that had been brought up to the Allied front line specially for this purpose.

DUKWs were amphibious vehicles capable of crossing rivers and short, calm stretches of sea - this one is at Salerno in 1943, probably September (credit: national Army Museum)

Training began on 24th December and continued to 26th when there was a conference to finalise the plan. Seven signallers from brigade HQ had been attached to the unit on the 23rd and would have been involved. A rehearsal was carried out behind their own lines on the night of 27th/28th.

On 29th December 1943 the commandos embarked on two ships, the Royal Ulsterman and the Princess Beatrice, troop-carrying ships that could launch landing craft.

The Royal Ulsterman, in sunnier weather than on 29th December 1943 - note the three landing craft (LCAs) strapped to her side at deck level. With three on the other side, and each LCA capable of carrying 36 men she would have landed approximately 216 Commandos

The LCAs were launched at 21.30 six miles from the intended landing place, still south of the Garigliano River; presumably this was to give the Germans no hint of the approaching craft. The plan was to land at 23.00, 1700 metres north of the river mouth. The weather was fair, according to the unit's war diary and visibility was 5 miles.

LCAs with troops in formation, in this case Canadians on D-Day 1944

But poor navigation meant they were going be landed while still behind Allied lines! Fortunately this was noticed, the little convoy changed course but even so at 00.30 they were still 1000 metres short of the planned landing place and 90 minutes late. The decision was made to land even though they were only 700 metres north of the river. Even then, one landing craft had a steering problem and could not land its troops.

The view from the sea looking east, showing approximate sites of the actual and planned landing places. The three targets are ringed in red. Note that I suspect the area is considerably more built-up than in 1943

Once ashore it took a further half an hour to establish their position; they then split into three groups, as planned.

120 men of 1 and 2 Troops made for Monte d'Argento. Given they had landed south of where they planned, had to cross irrigation ditches, wires and mined areas in the dark, they arrived about 03.00. While it is not stated in the accounts online, we can also see from the photos the next day (see below) that it was extremely wet and muddy.

They split into two groups, one to attack the hill, one to clear the houses and block the road to the north. German opposition was mainly to the north of the hill; four of the Commandos were killed.

Modern day Marina di Minturno, the north side of the Monte d'Argento which is the high ground with the trees - the sea is to the right of the photo, we are looking south

4 and 6 Troop attacked the area of the destroyed bridge. For similar reasons, they did not arrive until 05.00. They over-ran a pillbox and then set up ropes to cross the two 15 feet gaps in the destroyed road bridge back to the Allied lines. Captain Michael Long was awarded the Military Cross for his part in establishing the rope bridge. His citation says that efforts to cross in a rubber boat had failed. He swam to the first demolished bridge-pile despite the strong current, being under mortar fire and carrying one end of a rope. He than climbed the bridge pile and held the rope to allow the first men to cross. (source)

The remaining commandos cleared the spit of land in the river mouth but five men killed, apparently when a mine exploded.

There is a story that the party returning from Monte d'Argento nearly bumped into the party going to the bridge in the dark, which could have resulted in a 'friendly fire' incident; however, one of the groups (being Scottish) had a piper playing a distinctive tune which was recognised and the second group had their piper play a different tune, averting disaster. Did Commandos really take bagpipes on raids? If so, did they really walk around in the dark, trying not to alert the enemy but playing the bagpipes? We know there were signalmen attached but why weren't they in wireless contact? Having said this, it seems Private James Laing was injured when a mine exploded but was carrying bagpipes at the time (source).

Accounts refer to nine Commandos being killed. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission website allows us to name eight of them with a high degree of certainty:

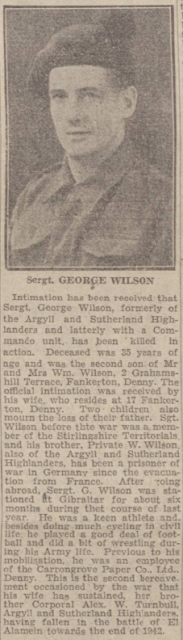

Lance Sergeant George Wilson

Lance Corporal Robert Crawford

Private Robert Sherwin

are all buried in Minturno Cemetery, run by CWGC

Serjeant Duncan Dundas

Corporal Francis Balneaves

Lance Corporal Alan White

Private Gilbert Reid Neilson

Signalman John Currie

have no known grave and are commemorated with others on the Cassino Memorial. It is possible the ninth man was Signalman Francis Lewis, also named on the Memorial.

This is the whole length of Stratford Street around 1900, now considerably shortened. The photo is taken from outside number 35 which is just out of shot on the left

Map from approx 1950 showing the area around Maryhill Central Railway Station (now Tesco superstore). Odd numbers on Stratford Street begin at 35, presumably the original plan was for it to extend to Maryhill Road

Comments

Post a Comment