John Hendrie Edwards

In his very readable autobiography, he describes the end of the 'Phoney War' on 9th April 1940 when the Germans invaded Denmark and Norway. Up to that point the squadron had flown bombing missions against specific military targets such as naval ports and seaplane bases. The invasion of Norway was across the Baltic Sea and the RAF bombers were to be used to fly at night and drop mines in shipping channels that would then settle in the sea and damage or destroy German ships which assumed the passage was clear.

This photo is from 1942 but gives an idea of what a mine looked like:

This is a photo of Hampden flying over the sea but again from much later in the war (and in Canada!):

Guy Gibson flew one mission on the 11th April. Then on 14th April he undertook the same mission, as one of four Hampdens; in one of the other planes was John Hendrie Edwards.

I can find very little about John. He was born at Camphill Lodge, Hillfoot, on 20th December 1919. This is not an easy building to pin down because villa names (like Camphill) do not convert simply into modern street numbers and because the numbering of some roads is not intuitive. But it was located on Boclair Road in Bearsden. I've ringed the building I suspect in red on the assumption for a building to be called a lodge it has to be closer to the road than the main house and this seems the only candidate:

His parents were William Summers Edwards and Sarah Abernethie (nee Hendrie) who had married in 1914. On John's birth record, William's occupation is "warehouseman" (someone who works in a warehouse).

In the 1921 Census we have a little more detail:

(1) John has an older brother, William - Sarah was the second wife of their father, William; his first wife was Annie Neil. Having given birth to William in May 1914, she died in February 1915, aged 21, probably of polio (the cause of death was given as "myelitis") while being nursed by her older sister, Agnes, at Geils Avenue, Dumbarton. (Many thanks to Mary Frances McGlynn, West Dumbartonshire Council Arts & Heritage Service, for identifying why Annie died away from home, and to Dr. Ken Paterson for offering a possible interpretation of the cause of death.)

(2) at the time of the Census, the family were in Dunoon - the 1921 Census was scheduled for early April but was postponed to Sunday 19th June, meaning some families were on holiday. The record does not tell us whether this was the family's permanent address. But I suspect it was only temporary (a holiday) for the third thing to note which is ...

(3) William was a warehouseman at Mann, Byars and Co. This is not a name we know today, the business closed in 1938 but it was located on the block now occupied by Marks And Spencer on Argyle Street:

Approximately the same view today:

Apart from the shop, Mann, Byars also had a factory in Virginia Street and William must have worked in the area - hence why I do not believe the family lived in Dunoon in 1921.

The Edwards family seem to have left Bearsden in the early 1920s as they do not feature on subsequent valuation rolls.

So we only know where John was in three days in his short life: the day he was born, on holiday (maybe) in Dunoon as a baby, the 14th April 1940 at RAF Scampton. The mission was to fly to Denmark and drop the mine in one of the shipping channels the Germans would have to use when sailing to Norway. This map shows the ports where the German invasion fleet siled from on the Baltic coast, especially Kiel for the navy; Oslo is right at the top of the map. The German ships had to pass through well-defined bottlenecks and this is where 83 Squadron were trying to lay the mines. Scampton in Lincolnshire is highlighted, as well as their target (the red circle by the D in Denmark).

The weather was poor but it was so important to stop the flow of German reinforcements and supplied to Norway (where the battle was in the balance) that it was risk worth taking and 40 bombers in all were sent, a large proportion of the RAF's resources at the time. Planes flew individually and carried out their own navigation. Gibson dropped his mine and turned for home. His account is worth quoting as John's crew would have been experiencing the same things:

"I shall never forget that journey. it rained all the way and was pitch black. Now and again the aeroplane became charged with static electricity and resembled a poor edition of Piccadilly Circus in peacetime. we had been diverted to Manston [in Kent, see map below, as had John's plane] and a south-westerly gale was blowing into our nose, making our ground speed a little under 100 miles an hour. After two hours we passed over the lights of Holland [still neutral at the time and hence not 'blacked out']. The another two hours were in front of us before we could see Manston. Most pilots when flying on instruments sometimes get the funny feeling that their instruments are giving false readings and they are quite certain that they are about to turn upside down at any moment. After a while I was no exception and I had repeatedly to shake my head, rather like a ballet dancer does when coming out of a pirouette, in order to keep myself upright.

Then we were getting QDMs [bearings to the airfield] from Manston.

Soon out of the low cloud and rain there suddenly came a green light, then another. it was Manston telling us to land, and we did not waste any time. This trip took nine hours, mostly on instruments. No wonder I didn't wake up until four in the afternoon next day.

Sylvo did not come back. He had got his QDMs but had gone floating down the Channel into the Atlantic; they never found him."

Sylvo was FO Kenneth Richard Hugh Sylvester and his crew was Sergeant Ernest Reginald Clarke (bomb aimer), Sergeant George Cyril Perry (gunner) and Leading Aircraftsman John Hendrie Edwards (wireless operator). A distress call, presumably from John as the wireless operator was received at 04.00; we know at this time another Hampden on the same mission crashed on a beach at Ryhope near Sunderland with its fuel exhausted. No bodies were found and they are commemorated on the Runnymede memorial:

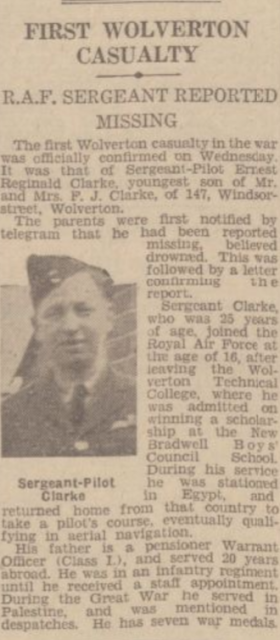

News travelled fast. The mission was on Sunday night and early Monday morning; by Friday, the local paper reported Ernest Clarke was missing:

Since I first published this post, I've been contacted by a member of Ernest's family who recalls him staying with them on leave from the RAF shortly before this final mission. As he said goodbye, he added "I don't think I'll see you again". They told him not to be so stupid and that he'd been on missions before, but he said "This next one is a really dangerous one, I don't think I'll be back." (Thanks to Susie White for passing this on.)

Guy Gibson, the indirect witness to John's last flight, died on 19 September 1944 when his plane crashed on a mission.

Comments

Post a Comment